Julie and I first met in our early twenties through an LA-based organization that advocated for undocumented Asian and Pacific Islander youth. Both undocumented, both artists. I first heard her sing at the Immigrant Youth Empowerment Conference. In front of hundreds of undocumented young people, families, and educators, she opened with a multilingual rendition (English, Spanish, and Korean) of “We Shall Overcome.” What followed was one of her earliest compositions,“Dreamer.” Acoustic and tender in nature, the song concluded: “Dream on, sweet dreamer. Your feet are bound, but your heart is free.”

“As a young adult navigating the stop-and-go process of life—which is a reality for many undocumented youth—I found peace and purpose in art. ”

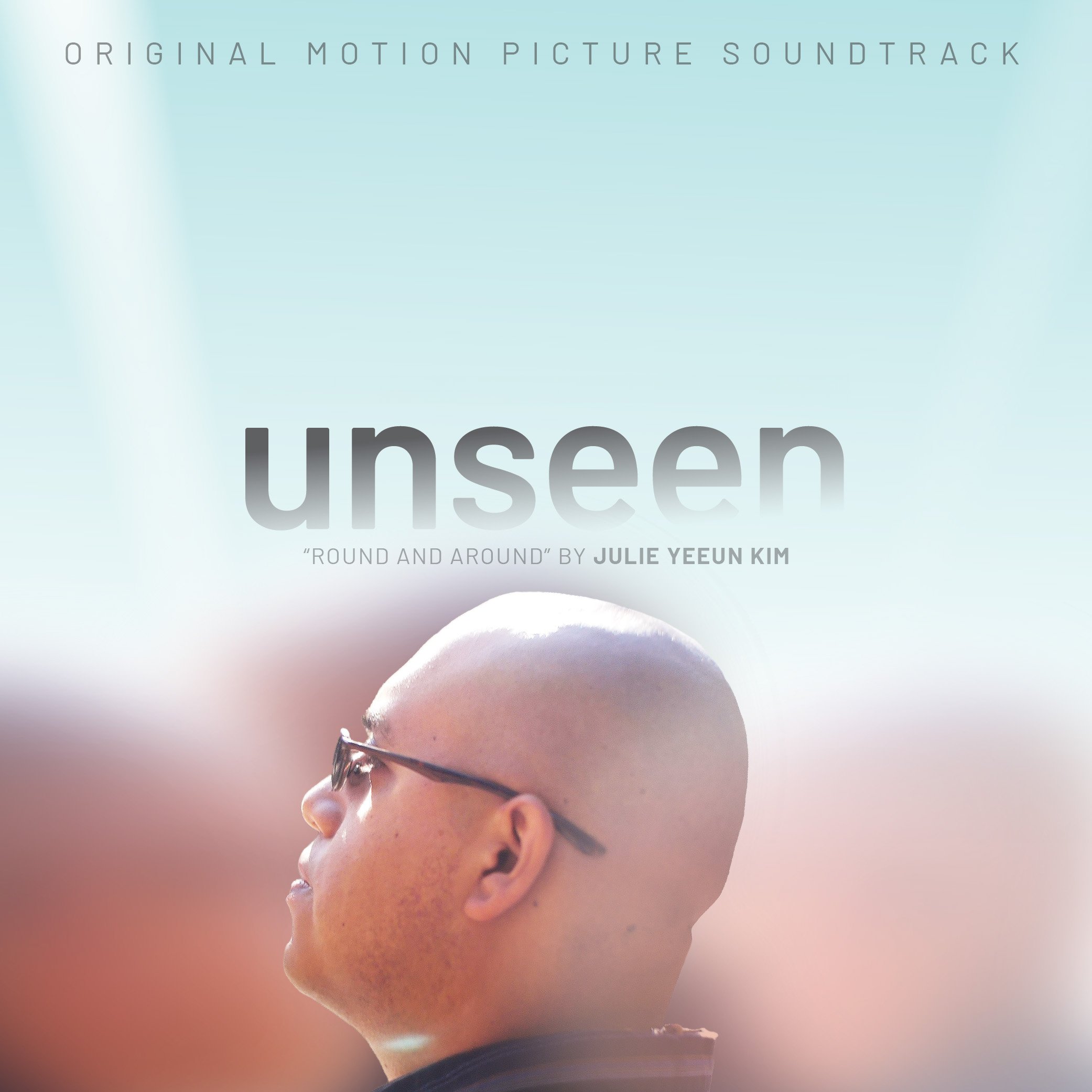

Years passed by, and Julie and I lost touch as she moved to the other side of the country. During that time, I sank my teeth further into the production of unseen with my friend Pedro, our protagonist. The film follows Pedro’s journey becoming a social worker, navigating uncertainties as a blind, undocumented immigrant. But at the heart of it, the film is more than just about the politicized identities Pedro inhabits. It’s really about vulnerability and finding ways to show others our most authentic selves. I wanted the film to fully reflect Pedro’s personhood, so I would ask him what kind of music he likes to listen to. He’d mention bands like Bon Iver and The Tallest Man on Earth; but in my mind, I would interpret it all as sounding like Julie’s song “Dreamer.” Through the process, I would ask our editor to use music from Julie’s discography as a temp soundtrack and, serendipitously, it all felt in sync. When I finally approached Julie to write a song for the film, I didn’t have to explain much—she understood Pedro’s sensibility. She went beyond immigration and disability, capturing all the film’s textures, in her song “Round and Around.”

***

When I was nine years old, first aware of my family’s undocumented status, I underwent a series of changes. Authorities were scarier. School became tougher. Sharing details about my life felt riskier. Friendships become harder, too—more burdensome and distant. Prone to the occasional word vomit, I put a tight rein on my tongue. It prevented slip ups, but it also prevented opportunities to connect.

Knowing the precarity of our situation, fearing exposure, I kept all but one friend in the dark about my status and told no one else until my twenties. But the desire to be known was just as tenacious. And so it was: I grew dissatisfied with all my relationships, despising the half-measures of intimacy yet fearing the necessary measure of vulnerability.

I’ve come a long way since I was nine. As a young adult navigating the stop-and-go process of life—which is a reality for many undocumented youth—I found peace and purpose in art. At first, I wrote stories, poems, and songs for myself, until I finally felt comfortable sharing them with friends. Eventually the audience came to include a small number of strangers on the internet who listened to my music or read my stories.

I first became vocal about my status in 2016 and, since, I’ve wrestled with the concept of the undocumented artist. Much of the harm of undocumented life happens under the hood of consciousness; our communities require a certain kind of person to notice and help untangle the painful knot of emotions, memories, and traumas that come with undocumented status and life in political and social liminality. Undocumented immigrants feel pain that often escapes diagnosis, with everyday speech and events triggering microaggressive wounds. Healing our community, I concluded, requires a creator who will be attentive to the invisible, verbalize the ineffable, and make sense of the illegible.

When Set approached me with the idea of writing an original song for unseen, I doubted whether I was the right person for the task. I had been paid to perform before, but I had never been commissioned to write a song drawing from my twenty years of undocumented life on my own creative terms. I had previously felt more like a guest telling a generic story about what people think undocumented life is like or what undocumented people might want to say. I knew this project would be different, and I knew I may never get the chance again. So I said yes.

Emily Dickinson once said “tell all the truth but tell it slant.” Slant is the secret power of the artist and storyteller. This is well-known. What’s far less known is that the undocumented artist has unique insights into slant storytelling. Our experiences resist articulation: the lack of legal and cultural language, the impermanence of the status and the always-pending state of arrest, the “pathways” that seem at once improbable and possible, and the aversion to self-disclosure for fear of being reported. All of these factors contributed to my silent orbits around life, particularly around relationships. All my life, I have been afraid to be witnessed, afraid to be held in another’s intimate knowledge. unseen is a reminder that on the other side of that fear lies a possibility that is worth my bet.

This film is a rare look at how undocumentedness (and queerness and disability) does not malform or deter friendships, as it had so often in my own life. Though we see relational pain, the film points us to another reality: vulnerability can be a precious currency making deep, meaningful friendships possible and desirable. The film is slant in aesthetic, content, and purpose, but this one message (among many) is clear: to be human is to be fragile. But to be fragile and loved is power.

The lead creative team assembled around Set and Pedro’s story also disrupts all manner of assumptions, all of us undocumented, formerly undocumented, or living with a disability. Miles away from the stereotype of incapability and incompetence, this team brought talent, resources, connections, wisdom, and love to the work. Set and Pedro’s friendship was like a central system inviting the rest of us not just into another work project, but into kindness and mutual growth. This is the sort of courageous, transformative, and inviting relationship that I wish I had been brave enough to encounter in my youth.

With the currency of friendship, what Set and Pedro created was nothing short of universal truths finding expression through (not despite) very particular details. That’s what good storytelling does. It reminds us that while different labels and experiences abound (whether political, social, or cultural), we are all here on this earth together to experience deeply, simply human moments. Whether undocumented, blind, or queer, each of us are worthy of love and friendship.